Advancing Metaliteracy: A Celebration of UNESCO’s Global Media and Information Literacy Week

Guest post by Trudi E. Jacobson and Thomas P. Mackey, co-editors of Metaliteracy in Practice and co-authors of Metaliteracy

Photo by Nathaniel Shuman on Unsplash

In the past year, the term “fake news” first began to be used broadly, as part of the immediate media analysis and critique of the way false information easily circulated during the 2016 Presidential Election. Previously, fake news referred to made-up or distorted news, as evident in the kind of comedy routines we see on TV or read about in satirical publications, either in print or online. But soon thereafter, the term fake news itself was appropriated in a new and more cynical way to attack prominent news sources that countered in any way the narrative of “alternative facts” being presented. Welcome to the “post-truth era” and one of the many literacy challenges we face in today’s connected world. The term “Post-truth” was the topic of a book by Ralph Keyes in 2004, but took on new relevance in 2016 to describe the proliferation of misleading and untruthful information communicated by the famous and unknown through social media and other sources. The 2016 Oxford Dictionaries’ identified “Post-truth” as the international word of the year, and describes a situation “in which objective facts are less influential in shaping public opinion than appeals to emotion and personal belief.”

This is the environment in which we celebrate and promote UNESCO’s Global Media and Information Literacy Week 2017, which runs from October 25 through November 1, 2017. A variety of terms are used for this crucial set of abilities and dispositions that help us to navigate through what are now particularly turbulent seas of information: Information literacy, media and information literacy, digital literacy, information fluency, and even Google literacy. Regardless of what it is called, having a command of literacies connected to information has taken on a critical importance for informed citizens in today’s complex and connected social media ecosystem. All of these approaches to literacy have value and advance critical thinking and learning in today’s world. We have contributed to this discussion by developing metaliteracy as a pedagogical framework for advancing critical and reflective thinking.

In 2016, we wrote an essay that addressed one of the significant concerns in a post-truth world and did so from an educational perspective. How can we learn to reject fake news in the digital world? focuses on the dangers of consuming, producing, and sharing false information. We argue that we need a reflective and participatory approach to address these challenges, given the unfortunate circumstances in which truth has been questioned in today’s political and social media environments. Because of metaliteracy’s emphasis on the active contribution of ideas in these spaces, we argued that, “Metaliteracy asks that individuals understand on a mental and emotional level the potential impact of one’s participation.” Doing so goes beyond effectively using the technology to seeing oneself as a responsible participant who carefully reflects on one’s own thinking and actions in these environments.

From our viewpoint, we are especially interested in exploring reflective learning as a way to empower individuals to continuously adapt to changing technologies while being responsible consumers and producers of digital information. Through this work, we are involved in expanding the roles of learners even further from consumer of information to participant, communicator, author, and researcher.

As an extension of these ideas, we focus specifically on several key components of metaliteracy in this blog post. Metaliteracy expands the understanding of UNESCO’s media and information literacy in our collaborative, social media-infused online environment with a focus on four learning domains. Yet metaliteracy and media and information literacy (MIL) have components in common, and strive toward informed, ethical, and engaged use and creation of information.

We have published several articles and two books about metaliteracy, including: Metaliteracy: Reinventing Information Literacy to Empower Learners (London: Facet and Chicago: ALA, 2014) and Metaliteracy in Practice (London: Facet and Chicago: ALA, 2016). As noted in the latter book:

Metaliteracy applies to all stages and facets of an individual’s life. It is not limited to the academic realm, nor is it something to be learned once and for all. Indeed, metaliteracy focuses on adaptability as information environments change and [on] the critical reflection necessary to recognize new and evolving needs in order to remain adept. (Jacobson and Mackey, 2016, xv-xvi)

Metaliteracy is more than a model to be applied in academic settings and is an approach to better understand our everyday experience with living and learning in today’s connected world. It is especially pertinent now that we have many opportunities to contribute and collaborate through social media while also being faced with so much misinformation and division.

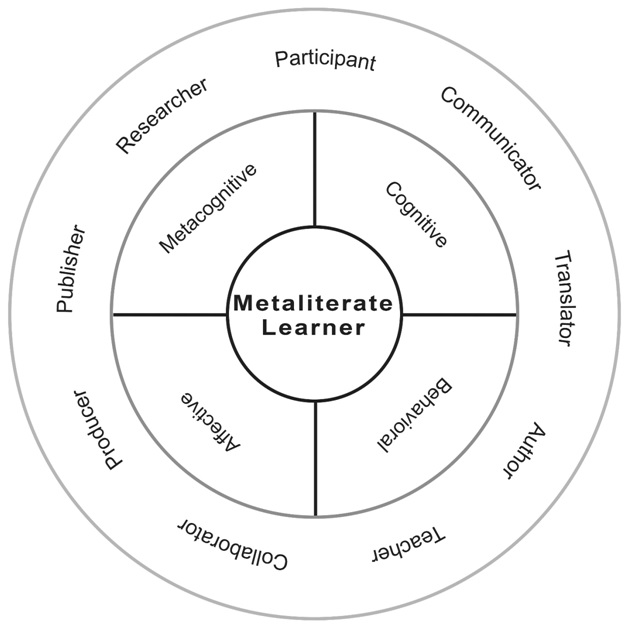

What might we learn from metaliteracy to help us through these trying times? Let’s start by examining this central image:

By organizing the rings around the metaliterate learner, this graphic emphasizes the importance of an ongoing desire to learn. As illustrated in this image, the metaliterate learner is a complex, whole person who engages in four domains of learning: metacognitive, cognitive, behavioral, and affective. This circular diagram shows that metaliteracy places an emphasis on metacognition, as seen in the upper left quadrant of the middle ring. Metacognition involves thinking about one’s own thinking, and self-regulating what still needs to be learned. But the other three learning domains are also important: the cognitive domain (the knowledge that comes with learning), the affective (changes in attitudes that accompany learning, as well as the willingness to have an open attitude), and the behavioral (what one is able to do following learning). The outer ring on the diagram shows the roles that learners take on in our participatory information environment, roles that should be informed by the learning goals and objectives. We are all learning all the time—there is no set point at which one starts to assume these active roles.

As we move to the outer ring, we see all of the active roles the metaliterate learner plays, empowered by a reflective core that includes an intersection of knowledge gained, changes in attitude, and ongoing development of abilities or proficiencies. The metaliterate learner is an active participant in social spaces, either in person or online, an effective communicator, using and adapting to technologies as needed, and a translator of information, moving from one form or mode to another, adapting and repurposing information and ideas through this process. In this context, the empowered metaliterate learner is an effective author of documents in various forms and both learner and teacher, exchanging these roles as someone who seeks and shares knowledge with others. This involves the learner role as collaborator of new knowledge, demonstrating the abilities to be an active producer and publisher of information. Because this work requires seeking and verifying information in many contexts, while asking good questions, the role of research is central to this approach, continuously evolving with the other interrelated roles.

The metaliterate learner diagram is informed by the metaliteracy learning goals and objectives that underpin the four domains of learning and support the metaliterate learner in the active roles. We encourage you to review the four goals and their learning objectives to gain a sense of their reach. As you consider them, note both the elements that extend beyond media and information literacy, and the abbreviations, which refer to the center ring in the diagram.

Also ask yourself the following reflective questions: Based on your own experience with today’s connected world, which role(s) have you played? Which roles would be especially helpful to encourage lifelong learners to play in today’s information environment?

With this understanding of metaliteracy, consider how it might inform navigating the fraught information environment in which we find ourselves. Being metaliterate means that we:

- Consider the format that information takes and the way in which it is delivered or shared: text, video, photos, statistics and other formats require the same scrutiny

- Critically evaluate how information is packaged and shared online and the extent to which professional-looking materials impact our perception of content

- Question the validity of information, regardless of source

- Observe our feelings when we engage with information that we do or don’t agree with

- Determine whether information is research-based or editorial

- Determine the value added by user-generated content

- Share information ethically and responsibly

- Reflect on our own beliefs in these spaces and challenge oneself to consider other viewpoints

- Always challenge our own beliefs and ask critical questions of information and of ourselves

UNESCO’s Global Media and Information Literacy Week is the perfect time to explore metaliteracy and then share what you learn with others. This is a critical time of engagement to fulfill the early promise of the Web and social media as open and participatory environments for collaboration, dialogue, and discovery. Recently we have seen the negative and destructive aspects of how these technologies have been harnessed as well, from fake news and alternative facts to an overall post-truth reality. These developments have challenged our own optimism and assumptions about these spaces as creative environments for producing and sharing knowledge. In any context, however, metaliteracy provides a critical and reflective approach to learning that supports an everyday practice of asking good questions, being an active and ethical digital citizen, while being open to new environments, technologies, and perspectives.

We invite you to continue the conversation as you delve further into metaliteracy and explore some of the questions we’ve raised in this blog. You can find us on Twitter @Metaliteracy and be sure to follow us at our own blog via Metaliteracy.org. We welcome all of your questions and insights.

Thomas P. Mackey, Ph.D. and Trudi E. Jacobson, M.LS., M.A. originated the metaliteracy framework to emphasize the metacognitive learner as producer and participant in social information environments. They co-authored the first peer-reviewed article to define and introduce this model with Reframing Information Literacy as a Metaliteracy (2011) and followed that essay with the first book on this topic Metaliteracy: Reinventing Information Literacy to Empower Learners (2014). This team co-authored the essay Proposing a Metaliteracy Model to Redefine Information Literacy (2013) and co-edited their most recent book for ALA/Neal-Schuman entitled Metaliteracy in Practice (2016). They are currently working on a new book entitled Metaliterate Learning for the Post-Truth World.

Trudi Jacobson, M.L.S., M.A., is the Head of the Information Literacy Department at the University at Albany, and holds the rank of Distinguished Librarian. She has been deeply involved with information literacy throughout her career, and thrives on finding new and engaging ways to teach students, both within courses and through less formal means. She co-chaired the Association of College & Research Libraries Task Force that created the Information Literacy Framework for Higher Education. Trudi is a member of the Editorial Board of Communications in Information Literacy. She freelances as the acquisitions editor for Rowman & Littlefield’s Innovations in Information Literacy series. Trudi was the 2009 recipient of the Miriam Dudley Instruction Librarian Award.

Thomas P. Mackey, Ph.D. is Vice Provost for Academic Programs and Professor at SUNY Empire State College. He provides leadership for the undergraduate and graduate programs at the college, including the School for Undergraduate Studies, School for Graduate Studies, School of Nursing, The Harry Van Arsdale Jr. Center for Labor Studies, the Center for Mentoring Learning and Academic Innovation (CMLAI), and International Education. His research interests are focused on the collaborative development of metaliteracy as an empowering model for teaching and learning. Tom is a member of the editorial team for Open Praxis, the open access peer-reviewed academic journal about open, distance and flexible education that is published by the International Council for Open and Distance Education (ICDE). He is also a member of the Advisory Board for Progressio: South African Journal for Open and Distance Learning Practice.

Reblogged this on Metaliteracy.org.

LikeLike